Bending stainless steel tube

Design benefits in engineering and architecture

Reprinted from Euro Inox with permission.

Author: Alenka Kosmač, Brussels (B)

Title photos: Patrick lints, Ghent (B), Condesa Inox, Vitoria/Álava (E), Thomas Pauly, Brussels (B)

Contents

1 Scope

2 Ways to achieve curved tubular designs

3 general parameters used in tube bending

4 Forming stainless steel

5 Austenitic – ferritic – duplex: differences in forming behaviour

6 Bending square and rectangular tube

7 When to heat before bending

8 Cleaning after bending

9 Summary

10 Glossary of terms

11 Relevant standards

12 References

1 Scope

The present publication is addressed to:

- designers who have to choose between different ways of achieving curved tubular parts or assemblies (welded/flanged/bent). The brochure highlights the advantages and practical implications of designs using bent tube.

- fabricators planning to sub-contract tube-bending work. The publication gives a basic understanding of the various processes, providing an overview of the options that may need to be discussed between customer and tube-bender.

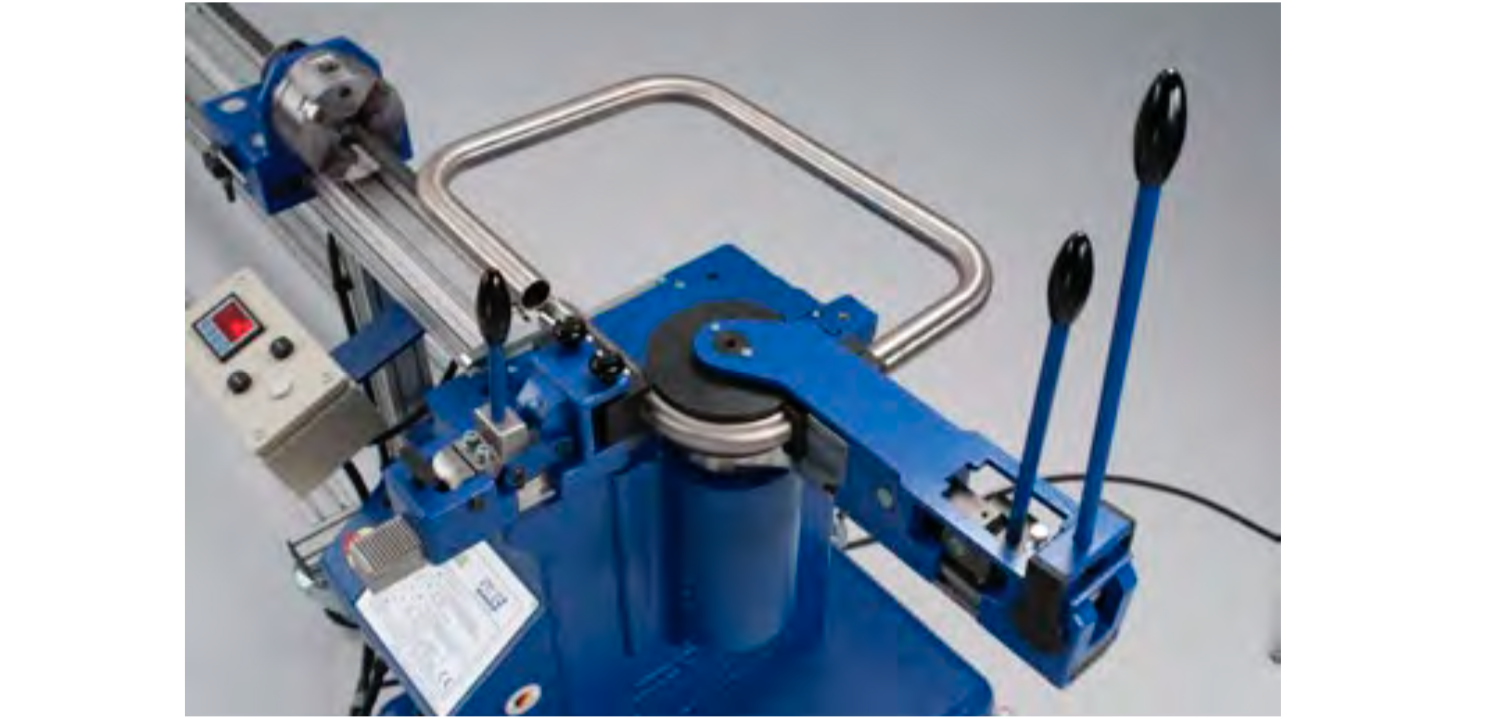

Typically the software of computer-controlled machines or the technical documents accompanying manually controlled machines provide reliable information about parameters such as minimum/maximum wall thickness, diameter and bending radius, the necessity of mandrels, overbending, etc. These need not be discussed in detail, therefore, in this publication.

2 Ways to achieve curved tubular designs

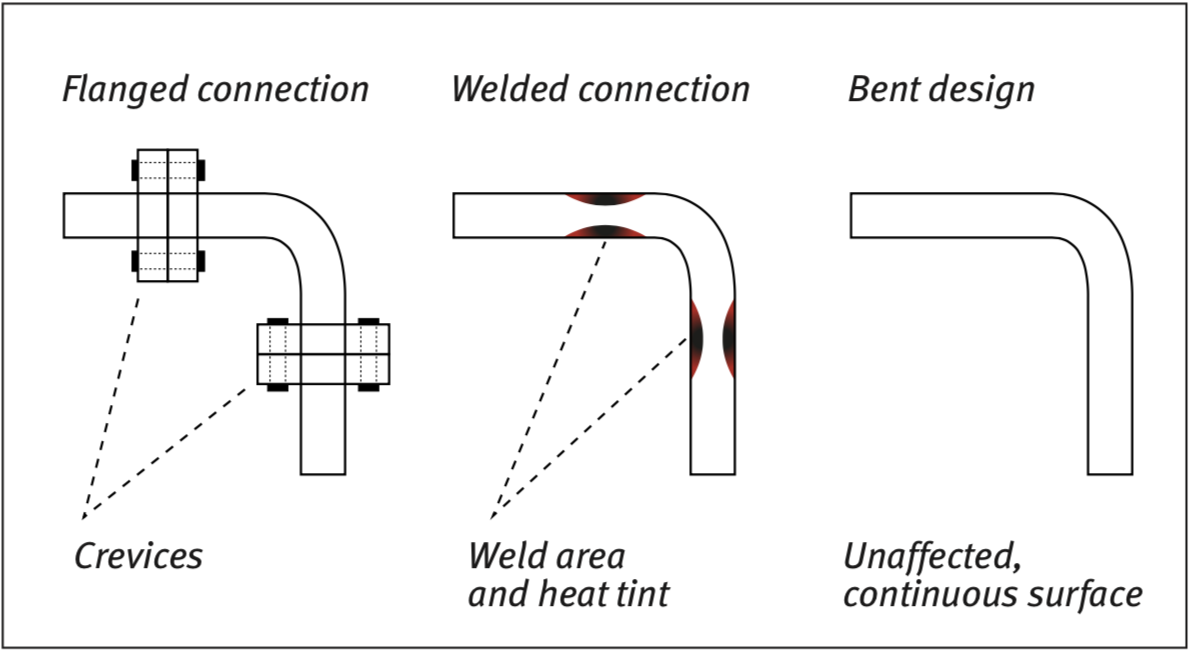

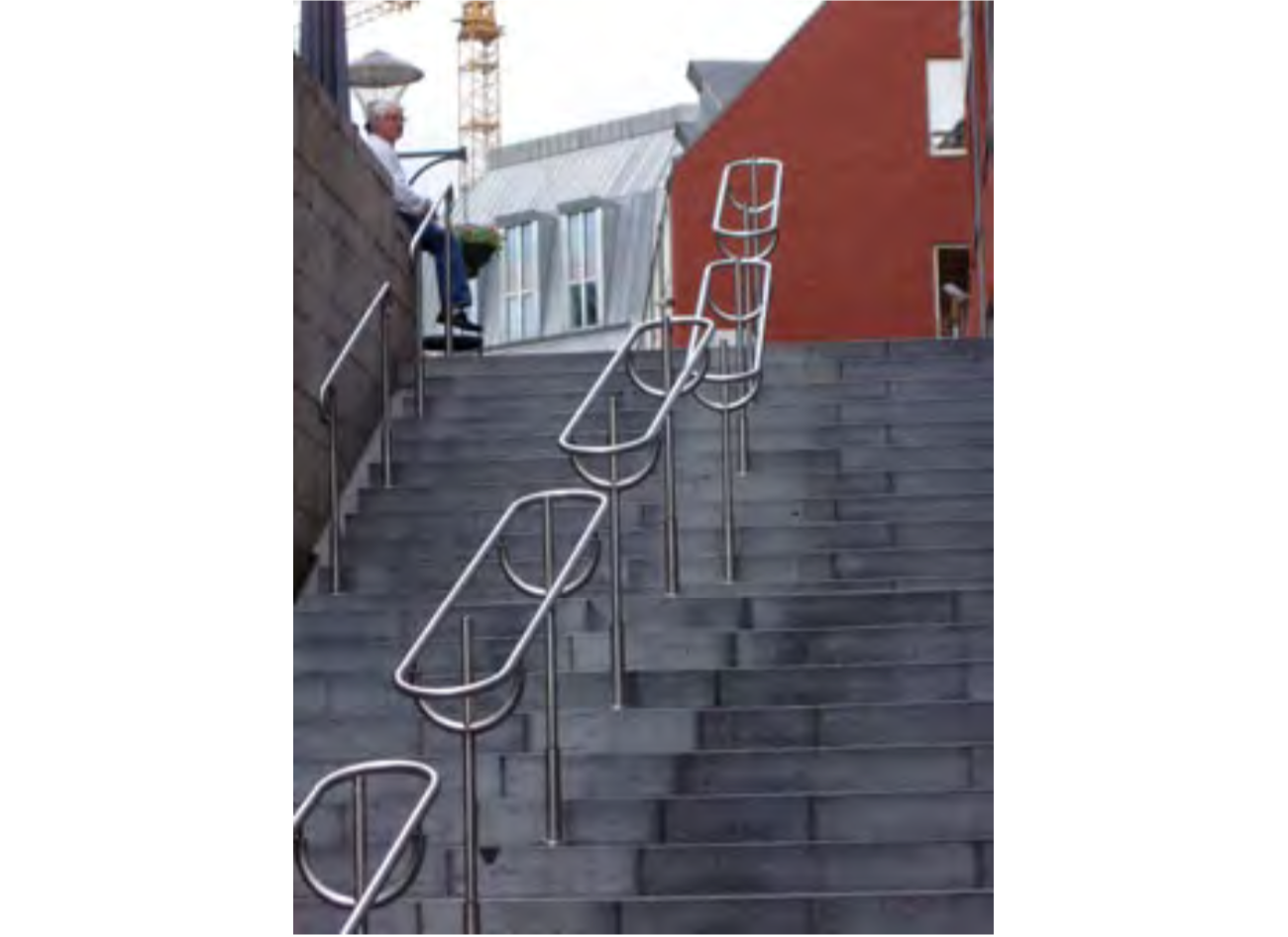

Designs using bent tube can be preferable to mechanical or welded connections for a number of reasons:

- Welded joints, for example between straight tube and elbows, require the prevention or removal of heat tint. Shielding gas may be difficult to apply, especially on site. The chemical removal of heat tint employs acid-containing products, usually involving environmental and safety precautions. Mechanical removal is only possible for the outside of the tube. A one-piece design in bent tube avoids these fabrication steps.

- In mechanical joints with couplers or flanges, crevices are inevitable. Depending on the conditions, these may be undesirable because they can trap corrosive substances. The risk of crevice corrosion must also be taken into account. Bent tube ensures a continuous, even surface.

Bent tube can therefore be the easiest and most efficient solution to a design task. Indeed, tube bending is one of the most frequently used fabrication techniques for stainless steels.

3 General parameters used in tube bending

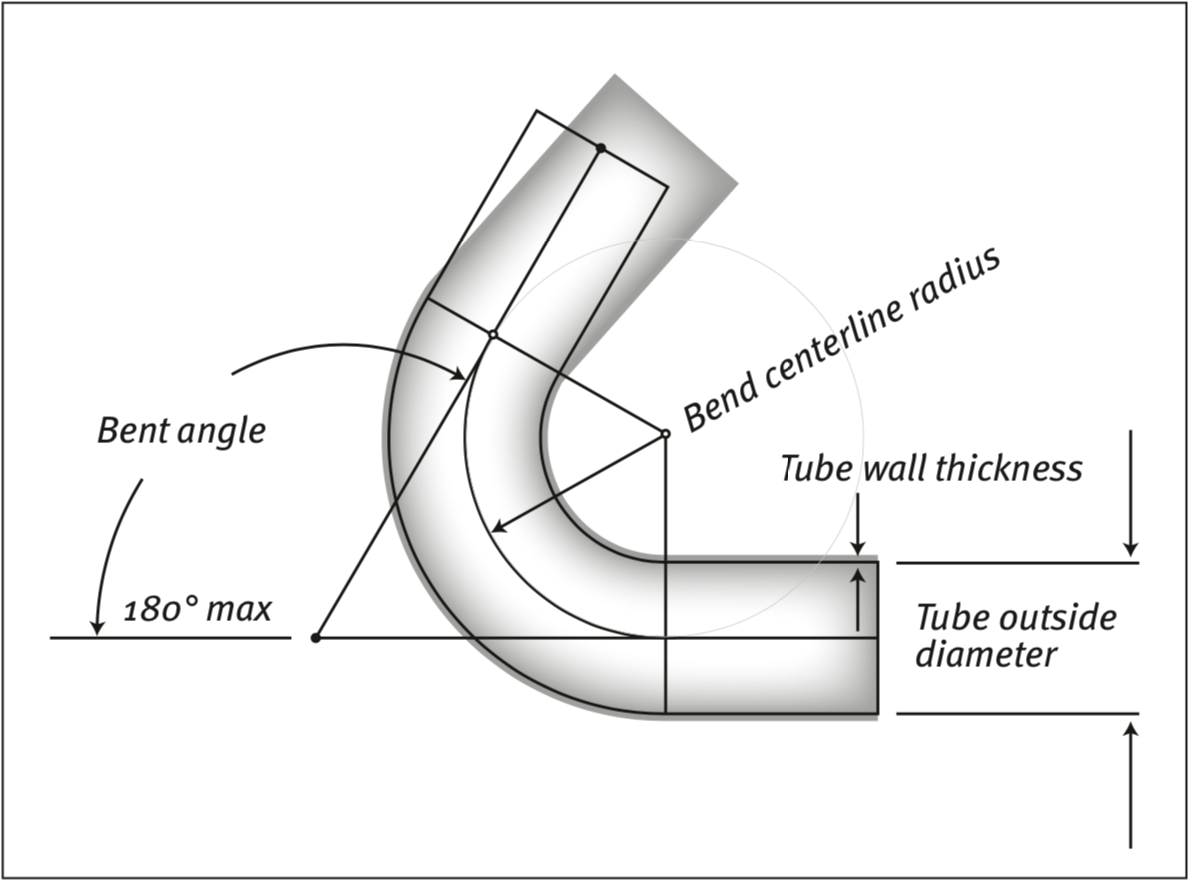

Most tubes are cylindrical, but oval, square and rectangular cross sections are also available [1]. A common objective in tube bending is to form a smooth, round bend. This is simple when a tube has a heavy wall thickness and is bent to a large radius. To determine if a tube has a thin or heavy wall, its wall thickness is compared to its outside diameter. This ratio is called the wall factor.

Wall factor = (Tube outside diameter) / (Tube wall thickness)

When wall factor is greater than 30, the tube is classed as a thin-wall tube. Wall thickness is a meaningless measurement if not related to tube diameter.

The same comparison is made to determine if a bend radius is tight or large (degree of bend).

Degree of bend = (Bend centerline radius) / (Tube outside diameter)

Two factors, wall factor and bend radius, are used to determine the severity of a bend. little or no support is needed inside the tube when the tube diameter is small and the wall is thick. As the tube diameter increases, the tube becomes weaker. If the wall thickness of the tube decreases this too makes it weaker. The forces acting on the tube also become greater as the bend centerline radius becomes smaller [2, 3].

In round stainless steel hollow sections, a rule of thumb for the tightest bend radius is the diameter multiplied by three. There is no corresponding rule for rectangular or square profiles [5].

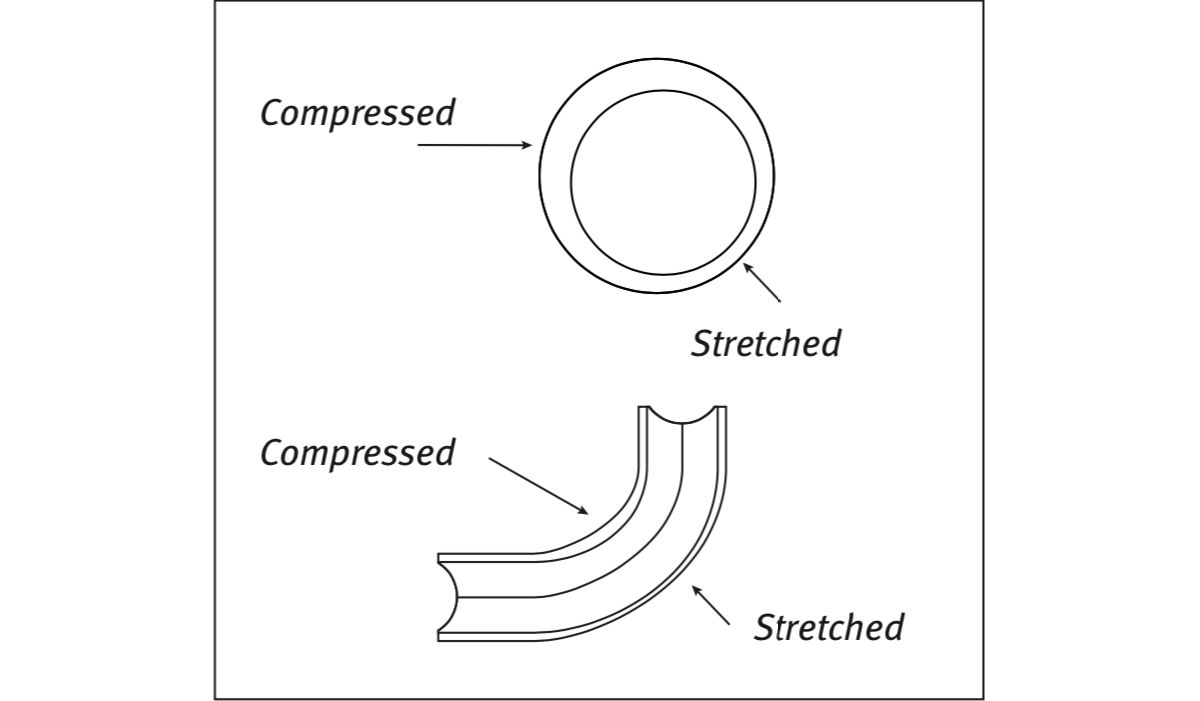

When a metallic tube is bent, two things happen. The outside wall reduces in thickness, due to the stretching of the material, and the inside wall becomes thicker. The material that forms the outside of the bend has further to travel and is therefore stretched, while the inside of the bend is compressed [2].

Unfortunately, all too often, bending requirements are not this simple. As the tube wall becomes thinner (the wall factor number becoming higher) and the bend radius tighter (the degree of bend number becoming lower) a distorted bend may result. To prevent this, a mandrel is required. The bend radius is also dictated by the end use, since it must create a shape which is both functional and aesthetically attractive [7].

4 Forming stainless steel

Forming stainless steel is very similar to forming other metallic materials. However, because it is often necessary to preserve the higher strength and surface finish of stainless steel parts, the techniques used in their fabrication are more exacting than those used for carbon steels.

The differences in the forming behaviour of stainless and carbon steel are specified below.

Ductility

A measure of a material’s ductility is its elongation at fracture. Austenitic stainless steels such as standard grades 1.4301 (304) or 1.4401 (316) have outstanding ductility. This value indicates by how many percent a standardized sample of a material can be stretched before it breaks. These values are:

- For stainless steel grade 1.4301 (304): typically more than 45%

- For carbon steel: typically 25%

In tube bending, elongation values deter- mine to what radii tubes can be bent. The more ductile the material, the narrower the bends can be. With stainless steel, the designer has great flexibility in determining bending radii. Elongation values of the grades in EN 10088-2 can be taken from the Tables of Technical Properties available from Euro Inox as a printed brochure or via an interactive online database on the Euro Inox website1.

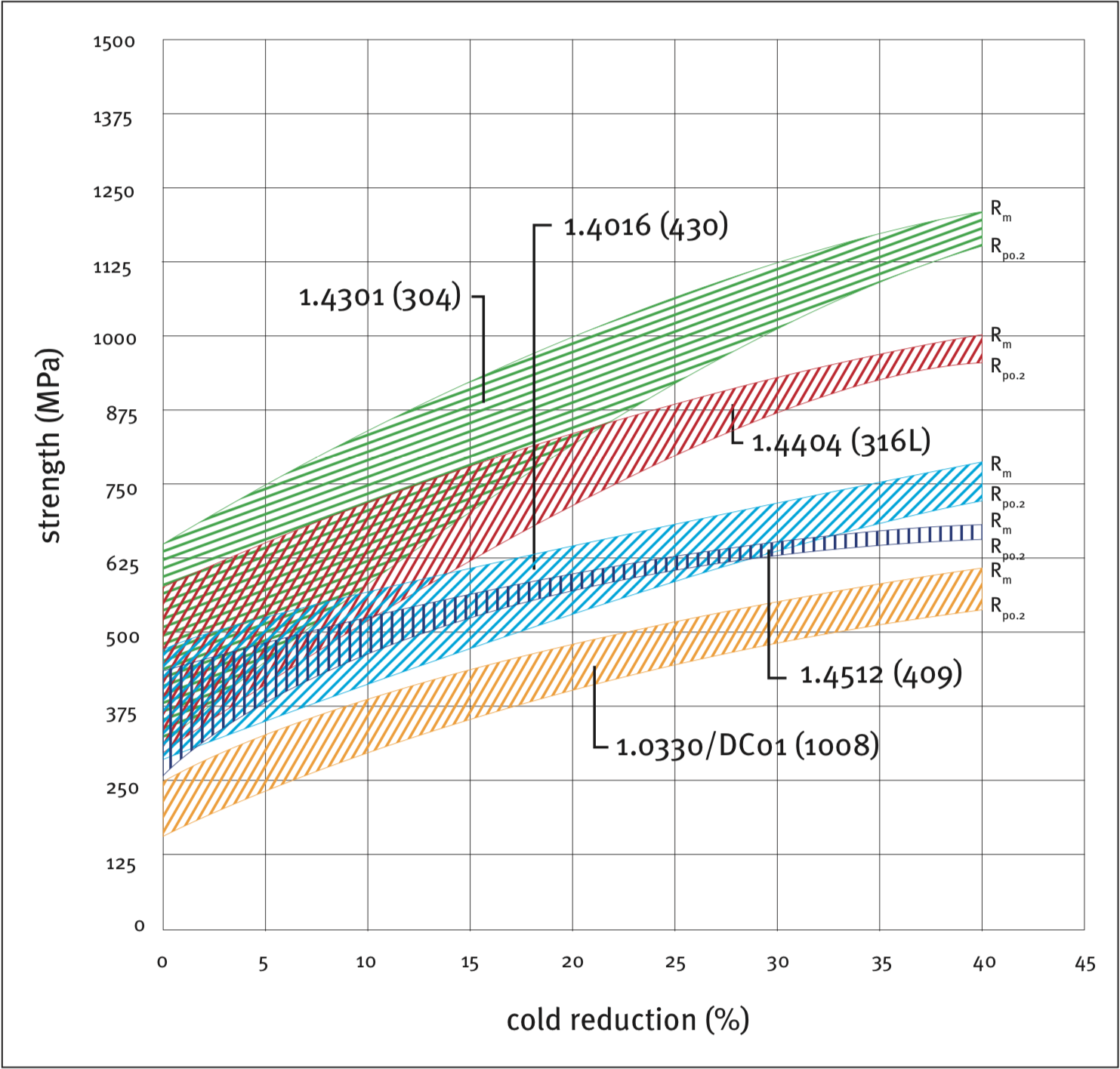

Work-hardening

Besides its ductility, austenitic stainless steel also has a pronounced work-hardening tendency, whereby when the material is formed its mechanical strength goes up. This work-hardening effect increases with both the extent and the speed of the forming process. In the case of tube bending this means that greater power is needed for stainless steel tubes than for carbon steel. Austenitic stainless steel requires about 50% more power than a carbon steel part of the same geometry (see Figure 4). When changing from carbon steel to stainless steel tube bending, it is therefore necessary to check that the bending machine is strong enough for the geometry concerned.

1 Stainless Steel: Tables of Technical Properties, Euro Inox, Materials and Application Series, Volume 5, 2007

| Tensile strength | Yield strength | Springback |

|---|---|---|

| is measured in tensile testing. It is the ratio of maximum load to original cross-sectional area. It can also be called ultimate strength. | is also measured in tensile testing. An indication of plastic deformation [9], yield strength is the ability of a material to tolerate gradual, progressive force without permanent deformation [10]. | is the term used to describe the tendency of metal that has been formed to return to its original shape. Springback will cause tube to unbend from 2 to 10 degrees, depending on the radius of bend, and may increase the bend radius of the tube. The smaller the radius of bend the less the springback [2]. |

Springback

Stainless steels have higher springback than carbon steels. Computer-controlled tube bending takes this factor into account automatically. In manually operated machines, the instructions give exact indications of the degree of overbending necessary to achieve the desired final geometry.

As a practical guide, the amount of springback is normally proportional to (0.2 Rp0.2 + Rm)/2, where Rp0.2 is yield strength and Rm is tensile strength. Springback can be controlled by overbending. For overbending, it is sometimes only necessary to make the punch angle smaller than the desired final angle of the workpiece [11].

The presence of the stabilizing elements niobium, titanium and vanadium,2 as well as higher carbon content, also exerts an adverse effect on the forming characteristics of austenitic stainless steels. The forming properties of grades 1.4541 (321) and 1.4550 (347) are therefore less favourable than those of 1.4301 (304) [11].

2 Cunat, P.-J., Alloying Elements in Stainless Steel and Other Chromium-Containing Alloys, Euro Inox

Table 1. Springback of three austenitic stainless steels bent 90° to various radii [11]

| Steel grade and condition (sheet) | Springback | for bend | radius of |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1t | 6t | 20t | |

| (302), annealed | 2° | 4° | 15° |

| 1.4301 (304), annealed | 2° | 4° | 15° |

| 1.4310 (301), half-hard | 4° | 13° | 43° |

| t = thickness |

Information comparing carbon steel and stainless steel is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Approximate forming data for carbon steel grades and stainless steel grades [12]

| Tube outside diameter | Approximate bend centerline radius | Carbon steel wall thickness min./max. | Stainless steel wall thickness min./max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions (mm) | Dimensions (mm) | Dimensions (mm) | Dimensions (mm) |

| 6 | 15 | 0.8 / 1.5 | 0.8 / 1.5 |

| 8 | 24 | 1.0 / 1.5 | 1.0 / 1.5 |

| 10 | 24 | 1.0 / 1.5 | 1.0 / 2.0 |

| 12 | 24 | 1.0 / 2.2 | 1.0 / 2.0 |

5 Austenitic – ferritic – duplex: differences in forming behaviour

As mentioned above, austenitic (i.e. typically chromium-nickel-alloyed) stainless steels have outstanding ductility. They are by far the most commonly used type of stainless steel in complex forming operations. Austenitic stainless steels are non-magnetic in the annealed condition, which is most often the supply condition. However, martensite transformation occurs during cold forming, which makes the steel slightly magnetic. The magnetic ferrite phase may also exist in longitudinal seam welds which are done without filler material or when a heat-treatment is not carried out after welding [5].

Ferritic stainless steels are becoming increasingly used, especially because they offer a cost advantage over austenitic grades3. In many respects, ferritic stainless steels act like stronger, somewhat less ductile low-carbon steels. Their work-hardening rate is similar to or slightly lower than that of low-carbon steel 1.0330/DC01 (1008) [11]. Ferritic stainless steels are successfully used in applications in which higher thermal conductivity is fully exploited.

Duplex stainless steel tubes are often used in process equipment4. This family of grades has a mixed austenitic and ferritic structure and is additionally alloyed with nitrogen. Duplex stainless steels combine high me- chanical values with high corrosion resist- ance. Their high strength is expressed in yield strength and tensile strength values [1]. These mechanical properties make in- creased bending power necessary. General- ly, duplex stainless steels require the same bending power as austenitic stainless steel of twice the thickness.

3 The Ferritic Solution. Properties, Advantages, Applications, ISSF, ICDA, 2007 4 Practical Guidelines for the Fabrication of Duplex Stainless Steels, IMOA, 2009

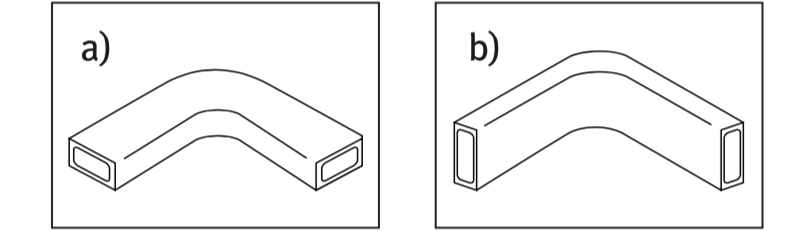

6 Bending square and rectangular tube

While the procedures are the same for bending round, rectangular and square material, square and rectangular tube requires special consideration.

Hard-way versus easy-way bending. When rectangular tube is bent, the material often has less distortion if it is bent the hard way (see Figure 5). The heavier the wall thickness, the tighter it can be formed without excessive distortion [13].

7 When to heat before bending

Most of the bends described so far have been performed by cold bending, where the workpiece is at room temperature. There are several advantages to cold bending:

- no heating equipment is required;

- the properties achieved in previous heat treatment are preserved;

- subsequent cleaning or descaling is less likely to be necessary;

- workpiece finish is of higher quality and no subsequent finishing methods are required;

- thermal distortion is avoided.

On the other hand, cold bending demands more energy than hot bending, for the same bend. There is more springback after a cold bend and more residual stress in the tube. Bends cannot be made to as small a radius in cold condition as can be achieved in hot.

Hot bending is used to make bends of small radius, adjacent bends with little or no straight tube between them, bends in material that has lower ductility in cold condition and bends that take too much power to bend cold. The disadvantages of bending tubes hot include high cost, slow production and poor finish on bends [14].

Because austenitic stainless steel tubing is stronger than carbon steel tubing and work hardens rapidly, warm forming (below recrystallization temperature) is also used. The temperature for warm forming should be kept below 425°C to prevent the formation of carbides.

Austenitic stainless steel tubing can be hot formed by heating to 1060–1260°C. Work should be halted when the tube has cooled to 925°C and the tube should be cooled rapidly, to minimize carbide precipitation.

Ferritic stainless steel tube, such as steel grades 1.4016 (430) and 1.4749 (446) is less easily formed than similar austenitic tubing. Ferritic tubing is hot formed at 1035–109°C and forming is stopped when the tubing cools to 815 °C. For best results, the 815– 980°C range should be avoided, since ductility and notch toughness are progressively impaired as the tube cools through that range. Ferritic stainless steel tubing is warm formed at 120–200°C.

At cooler temperatures and higher strain rates, ferritic stainless steels can fail in a brittle manner due to a lack of toughness. Carbon steels and ferritic stainless steels have a characteristic temperature or range of temperatures above which they can ab- sorb a large amount of impact energy and deform in a ductile manner. This characteristic temperature is known as the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature (DBTT). In forming ferritic stainless steels, the concern about unexpected DBTT cracking, particularly in colder winter months or in northern climates, has given rise to the following precautions [11]:

- It is advised not to form ferritic stainless steels when they are cold (winter conditions). The material should be stored in heated areas or intentionally warmed just prior to fabrication.

- If brittle fracturing occurs, consider moderate warming (20–60°C).

- If warming still leads to brittle-appearing fractures, consider reducing the rate of forming.

- Take the greatest cold-weather precautions when dealing with higher-alloyed ferritic stainless steel alloys (superferritics, 25–30% Cr).

- Take greater precautions with thicker materials (above 2.5 mm).

| Toughness |

|---|

| is the ability of a material to absorb energy and deform plastically before fracturing. It is proportional to the area under the stress-strain curve from the origin to the breaking point. In met- als, toughness is usually measured by the energy absorbed in a notch impact test [9]. |

8 Cleaning after bending

Lubricants used in bending can be fairly heavy. Great care must be taken when lightly chlorinated mineral oil is used. Since stain- less steels are not very resistant to chloride ions, additional cleaning may be required in these cases.

Any ferrous contamination on the surface could cause surface staining. This can occur very soon after installation, when the component is exposed to humidity in the air [5].

Particular care must be taken during each manufacturing step and the cleanness of the surface must be ensured before and after every work phase. For further reading on this topic please see the publications available from Euro Inox5,6.

5 Van Hecke, B., The Mechanical Finishing of Decorative Stainless Steel Surfaces, Euro Inox, Materials and Applications Series, Volume 6, 2005 6 Badoo, N., Erection and Installation of Stainless Steel Components, Euro Inox, Building Series, Volume 10, 2006

9 Summary

Forming stainless steels is very similar to forming other metallic materials. However, stainless steels have higher strength and ductility compared to carbon steels. Surface finish has to be preserved when working with stainless steels and the surface must be protected during manufacturing.

Austenitic stainless steel shows a characteristic work-hardening tendency. Work- hardening increases the yield and tensile strength of the material when cold worked. For tube bending this means that greater power is needed for stainless steel than for carbon steel tubes. As a rule of thumb, austenitic stainless steel requires about 50% more power than a carbon steel part of the same geometry.

When forming ferritic stainless steels, the risk of unexpected ductile-to-brittle transition-temperature (DBTT) cracking, particularly in colder winter months or in northern climates, has to be borne in mind. Ferritic stainless steels should therefore not be formed when they are cold (winter conditions). The material should be stored in heated areas, or intentionally warmed just prior to fabrication.

Duplex stainless steels are mostly used when high mechanical values combined with high corrosion resistance are required. These high mechanical properties make greater bending power necessary. Generally, duplex stainless steels require the same bending power as austenitic stainless steels of twice the thickness.

10 Glossary of terms

It should be noted that different expressions are often used for the same part of the equipment or procedure [2, 7, 15].

| Glossary | |

|---|---|

| Ball | A part of the mandel assembly that prevents the arc of the bend from flattening along the outside radius after the tube has passed through the point of bend. |

| Bend die | The forming tool used to make a specific radius of bend. The bend die usually consists of two separate pieces, called the insert and the bend radius. It is sometimes also called bend form or radius die. The essential specifications of a bend die are the outside diameter and the bend radius of the tube to be bent. |

| Bend radius | The radius of the arc of the bend. This is a general term that does not precisely specify the radius, therefore it can mean inside radius, centerline radius or any other arbitrary reference point. The preferred reference point is the centerline radius for round tubing and the inside radius for square and rectangular tubing. |

| Bend specification | The basic elements of machine, material and bend that define a tube bend application: shape, outside dimensions, wall thickness and material of the tubing, radius and degree of bend. Other elements may also be significant, such as a large weld seam or an extremely short tangent between bends. In most cases three basic parameters should be provided: tube outside diam- eter (OD), wall thickness (WT) and centerline radius (ClR). |

| Clamp die | The clamp die works in conjunction with the bend die to ensure the clamping of the tube to the bend die. There are two related specifications of primary importance in a clamp die: length and cavity texture. The shorter the clamp the rougher the cavity surface must be to maintain the strength of the grip on the tube. Serrations, knurling and carbide impregnation roughen the cavity surface, thus improving the clamp die’s grip. |

| Centerline radius (CLR) | The parameter given for the arc of a tube bend. Geometrically, it is the con- tinuation of the vertical centerline of the tube into the arc. |

| Degree of bend | Degree of bend = ClR/OD, also depth of bend. |

| Distance between bends (DBB) | DBB usually stands for the distance between bends. It is the straight sec- tion of the tube from tangent to tangent. Other expression for the distance between bends are “length”, “feed” or “position”. |

| Easy way (or E-way) | A term in tube bending for the orientation of a non-round tube shape relative to the plane of bend. In an “easy way” bend the major axis of the tube shape is perpendicular to the plane of bend. It is sometimes called an ”E-way” bend. |

| Hard way (or H-way) | The orientation of a non-round tube shape relative to the plane of bend – in a “hard way” bend the major axis of the tube shape lies in the plane of bend. |

| Inside diameter (ID) | This is the clearance of the tube. The outside diameter of a tube less twice the wall thickness. |

| Inside radius (ISR) | A specification for the arc of bend with non-round tubing. (The centerline radius, or CLR, is used to specify the bend of round tube.) |

| Mandrel | The mandrel is used to keep the tube round while bending. The major com- ponents of the mandrel are the shank and balls. Mandrel balls are required when bending thin-wall tube. Thicker wall tubes may be bent with compres- sion tooling (elliptical type) or bent using a plug mandrel. |

| Plane of bend (POB) | In multiple-bend applications, the tube acquires an orientation in terms of plane of bend upon completion of the first bend. All subsequent bends must be made relative to that orientation. This means rotating the tubing material a certain number of degrees relative to the plane of the previous bend. Plane of bend is often also called “twist”, “rotation” or “orientation”. |

| Outside diameter (OD) | Tube outside diameter – the standard way to specify the size of a tube or pipe as measured at its outside surface. OD corresponds to the bore diameter plus twice the wall thickness of the tube. |

| Pressure die | The pressure die is used to press the tube into the bend die and provide the reaction force for the bending moment. The pressure die will travel with the tube as it is formed. |

| Seam | The joint along the axis of tube at which the two edges of the original coiled material are welded together to create the tube. Usually the seam is only a matter of concern in tube bending if it has a weld bead that protrudes exces- sively into the ID of the tube and interferes with the mandrel. |

| Springback | The response of a bent tube to the removal of stress after the bending pro- cess. The key aspects of springback are material rigidity, degree of bend and wall factor. |

| Wiper die (or shoe) | A wiper die is used when a mandrel alone will not prevent wrinkling while bending a tube. The wiper die “wipes” wrinkles from the tube. It is mounted just behind the bend die. |

11 Relevant standards

| Standard | Title |

|---|---|

| EN 10216-5:2004 | Seamless steel tubes for pressure purposes – Technical delivery conditions - Part 5: Stainless steel tubes |

| EN 10217-7:2005 | Welded steel tubes for pressure purposes – Technical delivery conditions - Part 7: Stainless steel tubes |

| EN 10220:2002 | Seamless and welded steel tubes – Dimensions and masses per unit length |

| EN 10312:2002 | Welded stainless steel tubes for the conveyance of aqueous liquids including water for human consumption – Technical delivery conditions |

| EN ISO 1127:1996 | Stainless steel tubes – Dimensions, tolerances and conventional masses per unit length (ISO 1127:1992) |

| ISO 2037:1992 | Stainless steel tubes for the food industry |

| ISO 7598:1988 | Stainless steel tubes suitable for screwing in accordance with ISO 7-1 |

| ISO 1127:1992 | Stainless steel tubes – Dimensions, tolerances and conventional masses per unit length |

| ISO 9329-4:1997 | Seamless steel tubes for pressure purposes – Technical delivery conditions – Part 4: Austenitic stainless steels |

| ISO 9330-6:1997 | Welded steel tubes for pressure purposes – Technical delivery conditions -- Part 6: Longitudinally welded austenitic stainless steel tubes |

12 References

[1] http://www.jorgensonrolling.com/pipebending.html

[2] http://www.hinesbending.com/BASICTUBEBENDINGGUIDE.pdf

[3] Vaughan, M., Leonard, E.-E., Tube International, Nov. 1995, http://www.summo.com/tube.pdf

[4] http://www.woolfaircraft.com/prebent.html

[5] Stainless Steel Hollow Sections, Finish Constructional Steelwork Association, 2008

[6] Mandrel Bending Basics, http://www.hornmachinetools.com/pdf/tube-bending-guide.pdf

[7] http://www.summo.com/tube.pdf

[8] ASM Specialty Handbook, Stainless Steels, J.R. Davis, 1994, p.258

[9] Chandler, H., Metallurgy of the Non-Metallurgist, ASM International, 1998

[10] http://www.toolingu.com/definition-650200-77305-yield-strength.html

[11] ASM Handbook, Vol.14B, Metalworking: Sheet Forming

[12] Swagelok, Hand Tube Bender Manual, http://www.swagelok.com/downloads/webcatalogs/en/ms-13-43.pdf

[13] Smith, B., King, M., Bending Square and Rectangular Tubing – Modern Science or Ancient Art?, http://www.bii1.com/library/TPJSquare.pdf

[14] ASM Handbook, Vol. 14, Forming and Forging, pp. 1457-1477

[15] Miller,G., Justifying, Selecting and Implementing Tube Bending Methode, http://www.vtech-1.com/articles/primer.pdf